Isn’t it a little suspicious that the only true religion is the one with which we happened to grow up?

—Rachel Held Evans, Evolving in Monkey Town

Most fundamentalists naïvely think their form of Christianity was lifted intact from Jesus of the first century.

—Calvin Mercer, Slaves to Faith

Christianity “is a historic faith that relies on the credibility of its theological formulations and its Scriptures.” Its “beliefs are founded on what is believed to be historical facts–not merely on myths or moral stories” (Tucker 2002, 118). “It asks the faithful to believe certain historical events took place, like the prophesied virgin birth of Jesus, his reputed miracles, his teachings as told to us by ‘inspired historians,’ his death on the cross, his resurrection from the dead, and his ascension into heaven” (Loftus 2008, loc. 3077-80). Conservative Laestadianism takes that historical dependence to an extreme degree with its claim to be the latest (and in the mind of many believers, the last) in an unbroken chain of incarnations of God’s Kingdom on this earth. Each link in the chain depends on the personal transmission of the gospel via the proclamation of the forgiveness of sins “from faith to faith.” Thus there is considerable pressure on the church to provide a plausible history of its spiritual heritage.

Typical believers tend not to concern themselves too much about the details of this history, seeming rather to take comfort in a widespread feeling that elders and historically minded individuals in the church have it all figured out. Decades ago, before undertaking my own historical investigations, I remember being fascinated and inspired by hearing gray-headed members of the flock refer to Laestadius’s conversion in the presence of “Lappish Mary,” to the spirit “burning as fire in the snow” during the early years of the Laestadian awakening, to some Pietist “readers” who had kept the candle of God’s Kingdom burning dimly before then, and to Luther being a believer just like we were. Things got pretty vague further back than that, though. We all understood that the Holy Spirit had to have been carried in the hearts of believers from Luther to Laestadius, but nobody had the faintest idea how it happened.

And of the time before Luther nothing was known beyond a supposition that there were true believers hidden somewhere within the Catholic Church (see 5.1) and some cautious optimism that John Huss had been one of God’s Children. This lack of information and even interest in such information was made clear to me when I wrote an article about Luther and the Reformation for an issue of the Voice of Zion (5.4.1) and proposed a paragraph mentioning some possibilities for “believing” predecessors to Luther. One of the several editors of the article, a widely respected, historically-minded LLC preacher, rejected the paragraph, saying that such speculations were interesting material for discussions in the sauna but not appropriate for a church publication.

The same dim level of awareness is widespread in the church concerning the many Laestadian splinter groups that travel separately, rejecting each other but all claiming spiritual fellowship with the same founders of the movement. To the average Conservative Laestadian, they are all just “heretics,” differentiated from each other and the true faith by a few mere sentences of caricatured summary about their beliefs. Most know about the “last heresy” of 1973 because they or their parents lived through it, but its cause is mostly chalked up to “leniency,” which mostly involved a desire to accept television and organized sports for schoolchildren, and some obscure theological issues. Some are aware of the “Kirkkokunta” and “Esikoinens” but very few know anything about those groups or what precipitated the schisms between them and Conservative Laestadianism.1

Church history is an obscure and arcane topic. I certainly don’t blame anybody for not taking the time to research it, or even have an interest in it. But without investigating it for myself, I personally was unwilling to claim myself as one of 100,000 or so of the only true Christians, the sole heirs of Christianity’s vast spiritual and cultural legacy over the course of 2,000 years. For those readers who have made that claim as current or former Laestadians, the following discussion about our spiritual heritage will be of interest and significance. Other readers with a more general interest in Christianity and the Bible might find their eyes glazing over from all the historical minutia, and may wish to skip ahead to 4.2.

For Luther, the greatest good which the [Christian] community possesses is that forgiveness of sins is to be found in it.

—Paul Althaus, The Theology of Martin Luther

Three essential links in the chain of Conservative Laestadianism’s spiritual heritage are the Apostle Paul, Luther, and Laestadius. Of those three doctrinal fathers, Martin Luther is the one who has left the most written evidence of his beliefs. His collected works occupy over 100 volumes, spanning subjects from Adam’s creation to Zwingli’s heresy. And yet Conservative Laestadianism, whose American denomination is called the “Laestadian Lutheran Church,” pays almost no attention to what the man had to say. Indeed, there is some apprehension about delving too deeply into his writings, as exemplified by the following quote from the January 1980 Voice of Zion:

† “In some of the homes of the children of the kingdom are seen volumes of Luther’s Works. These have been translated into English by what we may call modern scribes of a dead faith. Consequently, as edited versions, the living truths of the gospel of the kingdom have been sometimes diluted.” These “translated versions have a significance to a child of God only as a reference, and are supplementary to the current publications of God’s Zion. They are recognized to be of value only by those already in faith, unless they are influential in awakening lost souls. More often, many read Luther, Laestadius, or other reformers who were in faith and who wrote voluminously, only to find that their own preconceived notions of unbelief have been reinforced. The word as read does not benefit them, not being mixed with faith.”

What the quoted writer had probably become aware from his own reading is a little known fact among Conservative Laestadian believers: there are real and significant conflicts between important doctrinal positions of the church and the teachings of Luther. But those conflicts cannot be dismissed as the result of mistranslations. Having heard that excuse many times in decades past, I went to the trouble of becoming somewhat fluent in Luther’s German for the express purpose of skipping the widely suspected step of relying on others’ translations. The result was not learning penetrating insights that were unavailable to English readers of Luther, or uncovering deceit by “modern scribes of a dead faith,” but a realization that the translations faithfully convey Luther’s teachings, and those teachings must be reckoned with.

Another way that some have attempted to deal with inconvenient Luther writings is to assert that they were written before Luther’s conversion, or altered after his death. Neither assertion is tenable. Almost all of Luther’s writings are from after his revelatory “Tower Experience” in the Wittenberg monastery around 1518, which was itself several years after his conversion experience in the Augustinian monastery at Erfurt. And the charge of changes in his writings is easily dismissed by that fact that those writings were widely circulated and scrutinized immediately upon publication. Luther’s forceful personal presence and the diligence of his wide circle of supporters would have made short work of any attempt at forgery. (Ironically, the theological writings whose authenticity and accuracy are most suspect from a purely historical and scholarly basis are found not in the works of Luther or Laestadius, but in the New Testament.)

In my studies, I have also found some amazing commonalities with Luther. Despite the passage of nearly five hundred years, Conservative Laestadians follow Luther’s teachings about personal absolution to a degree that is remarkable, especially considering how little attention has been paid to his writings within the movement. I will always remember one day some fifteen years ago when I read the words Vergebung der Sünde (forgiveness of sins) in a musty old book containing some of Luther’s sermons in their original German and realized that the personal preaching of such forgiveness was not just a Laestadian invention after all. (It may well be a Lutheran invention to a great extent, but that is a topic for later, in 5.1.2)

What links of the chain connect Luther back to the Apostle Paul? In the words of Paul Althaus, Luther himself thought that

God has always preserved his church, even under a church organization such as the papacy which erred in many ways. He has done this by marvelously preserving the text of the gospel and the sacraments; and through these many have lived and died in true faith. This remains true even though they were only a weak and hidden minority within the official church. [1963, 343]

The Voice of Zion made a similar claim in its July 2008 issue:

† “During Luther’s time the main message of the Bible was lost in the teachings of the Catholic Church, which taught that salvation was attained by a combination of faith and good works. After his conversion, Luther finally understood that a merciful God is to be found without one’s own merits and that the central message of the Bible was salvation alone by grace, alone by faith, alone through the merits of Christ. We agree with Luther’s telling statement: ‘Christ is the Lord and King of the Bible.’”

But the Conservative Laestadian teaching is that the Holy Spirit and its power of the forgiveness of sins must have been passed on directly from believer to believer since Christ gave it to the assembled disciples. To me, that makes the question a vexing one. Just where were those true believers before Luther’s conversion, even in the years immediately prior to that pivotal event? I discuss this, along with the various conflicts and commonalities I’ve found with Luther, in Section 5.

We have strange difficulties to meet in Lapland, and one of them is a sect called “Loestadians,” who believe that they are the only people who are going to heaven.

—Andrew Wangberg, Bible Pioneer Work in Norwegian Lapland

The third link is Lars Levi Laestadius, whose importance to the movement bearing his name is summarized on the About Us page of the LLC website:

† “The Laestadian Lutheran Church takes its name from Martin Luther and Lars Levi Laestadius. The name of the reformer Martin Luther and his teachings are well known around the world. The name of Laestadius is less familiar. Lars Levi Laestadius was a Lutheran pastor who served in northern Sweden from 1825-1861. In 1844, after nineteen years in the ministry, Laestadius was helped into living faith by a woman named Milla Clementsdotter, a member of a group known as ‘Readers.’ Following his conversion, Laestadius’ sermons were instilled with a new power, the power of the Holy Spirit. . . . The teachings of Laestadianism are based on the Bible and the Lutheran Confessions.”

Despite his significance to Conservative Laestadianism, the vast majority of its adherents know nothing about what Laestadius actually preached and taught. He is almost never quoted or discussed beyond brief historical summaries of his conversion and the early Laestadian awakening. There’s probably a good reason for that; the harsh and crude tone, unrelenting legalism, pagan superstition, and sexual imagery and content found throughout Laestadius’ sermons are shocking and deeply disturbing, at least to me. And the sermons in question are almost all post-1844, authored by the post-conversion Laestadius who is considered to be a brother in the same living faith.

Just imagine the following passages being read in church today:

[T]he merciful Lord Jesus who is the true Father of all poor orphan children lift up these helpless naked wretches from the cold floor of the world; He will wash them clean with the water of life; He will take them into His lap and teach them to suckle at His breasts of flowing grace, yet not so fast that the milk of grace should cause them to choke, but only as fast as the wretched ones are able to swallow. [Farewell to Karesuando Congregation, 1849]

God laments through the prophet Ezekiel that Israel is one spiritual whore, who committed adultery with many idols and allowed the Egyptian whorebucks to squeeze her breasts. So also the devil’s whore has allowed the devil to squeeze her breasts and has lain in the bosom of the devil for many years, and has committed adultery with many idols. She has committed adultery with so many that she has finally become unfruitful or an inappeasable harlot. Such an inappeasable harlot does not become fruitful, although she would lie near the Holy Spirit every night. And how could tribulation of birth come to such a one who is unfruitful? And such unfruitful ones and inappeasable harlots are first the wise of the world, who look at the effects of the Holy Spirit as the effects of the devil’s spirit. The devil has squeezed their breasts so long, that they have hardened. [Third Sunday after Easter, 1850]

We know that not one woman will become fruitful without a seed. So also God’s congregation, which in the Scriptures is compared to the bride of the Saviour, cannot become fruitful without seed. The bride of the Saviour becomes fruitful when she lies near the Holy Spirit or in the Saviour’s lap; He then pours the incorruptible seed into the heart of the bride. And if that person, into whose heart this incorruptible seed is poured, is a pure virgin, she would immediately become fruitful. But there is no other pure virgin than the virgin Mary. All others are the devil’s whores and some have committed adultery with so many, that they have become unfruitful. . . . Are you, devil’s whore, worthy to bear the crown of glory? . . . When you have no longer been acceptable to the devil for a whore, the Saviour took the devil’s whore for His bride. The devil’s angels spit upon her and said, “Is that the kind the bride of the Son of God is, who now shamelessly barks at honorable people?” One naked, scabby, and old whore, full of smelly wounds from which the pus of deviltry runs, is no longer acceptable to the devil for a whore, what then for a bride for the Saviour. [Third Sunday after Easter, 1850]

[W]hen a naked whore wants to live very meekly, she removes her sack-cloth shirt from herself and in place puts on a cambric shirt, through which the moon and the sun shine. On top of the cambric shirt she puts on a crinoline skirt, and so beautifully decked she goes to dance with the whore bucks, so that they would see her beauty. Both breasts she leaves uncovered for pleasure for the eyes of all those who desire to look upon her, but the moon and the sun shine through her clothes, and when she comes into the sunlight or before a candle, all the shameful places are seen, although she has meekly covered those shameful places with finery. . . . If she was so wise that she would wear clothes of skins, which God made for Eve, the shameful places would be covered better. [Twentieth Sunday after Trinity, 1850]

Woe, woe! Children, take heed that the blood which is in your heart and in your veins has come from the Parent’s heart. Should you mock the Parent’s tears anymore, you who have received blood from the Parent’s heart, which sustains your life? And the heavenly Parent must still suckle you, He must allow you to suckle His grace flowing breasts so that the weak life which is in you would remain with you. Remember now, children, these tears of the Parent, which today have flowed from His eyes because of you and all ungodly children. [Tenth Sunday after Trinity, 1851]

What living beings are they who love darkness? All those people who live under the earth, as elves and earthlings and bastards who screech in the dusk and frighten the living and those people who live upon the earth. So also the magpies and forest devils who laugh at and curse the light. . . . Have you not heard how elves steal the children of men before they are baptized, and even afterwards they exchange the children of men on whose breast a cross has not been placed? For elves cannot bear a cross to be placed upon the breast of their children; elves surely swaddle their children, but it is not allowed in the kingdom of the elves that the swaddling bands would be put to cross upon the child’s breast. It is well known from that, that elves are enemies of Jesus’ cross, and how could the elves carry the cross, who eat devil’s dung and the manure of old adam. After that drinking they are so filthy and drowsy, as if they would have eaten dung, but just the same they consider devil’s dung sweet although it stinks as poison a quarter of a mile away. [Second Pentecost Day, 1854]

[W]hen the groom tarried, when death did not come quit then after the first sign of grace, then the first zeal began to end, carrying the cross became troublesome, that female devil, the world, began to show its beauty to them, as the world’s whores bare their breasts to the whore bucks, so this female devil the world, bares its breasts of fornication to the Christians and entices them with its beauty. [Twenty-Seventh Sunday after Trinity, 1856]

The proclamation of the forgiveness of sins in Jesus’ name and blood is central to Conservative Laestadian preaching. Yet it is a little-known fact in the movement that Laestadius himself was reluctant to accept the use of that proclamation. He “feared dead faith so much that he did not dare to comfort very much” (Kulla 2010, 129). Jussila claims that Laestadius and Raattamaa “were united with the closest of bonds in the same doctrine and spirit, although with different gifts” (1948, 28). But he admits that it

† “has been known to us and to all the people of the Lord that Laestadius was so eagerly chasing the wolves that he would forget to feed the sheep. It is also known that at first he was [so] aghast over Raattamaa’s preaching of the remission of sins that he said: ‘Now all the scoundrels are accepted into the Kingdom of God.’ But he found it easy to believe and comprehend the words of the Lord Jesus: ‘Whosoever sins ye remit; they are remitted unto them.’ And when he noted that this is the office of the Holy Spirit, which it exercised through those people who have received its gift, then he also rejoiced over this discovery” (p. 29).

I have found one early sermon of Laestadius that does contain an absolution proclamation of sorts: “So believe now, you palsied one, that your sins are forgiven” (Nineteenth Sunday after Trinity sermon, 1847). See the full quote in 4.6.2. It is such a rare find in his law-oriented writings, especially given the early date, that one might be excused for wondering about the authenticity of the passage. Another bit of absolution language “in the name and blood of Jesus” is contained in an 1849 Laestadius sermon whose manuscript authenticity is suspect (Hepokoski 2002a, 38; Leivo 2005, 129).

As long as Raattamaa lived the Laestadian revival was outwardly one unit in Europe. Although there were undercurrents of differences, Raattamaa was a respected and well beloved elder to whom all submitted.

—Carl A. Kulla, Journey of an Immigrant Awakening Movement in America

Juhani Raattamaa was “the most notable of Laestadius’ disciples. He had been presented with the lofty gifts of the Holy Spirit” according to Heikki Jussila, a Conservative preacher [1863-1955]. In his 1948 autobiographical book The Grace of the Caller, he quoted approvingly the following summary of Raattamaa originally written in 1873:

† “He has been gifted with that spirit of wisdom and knowledge which, free of bias, understands how to preach all of the doctrine of salvation fully, and correctly divide the word of truth–he has during the entire time of this Christianity [preached] with greatest exactness both freedom from the law of Moses and the law of Christ in the congregations” (p. 39).

Jussila also lists other “messengers of Laestadius and preachers of Finland,” including Juhani Raattamaa’s brother Peter, Erkki Antti Juhonpieti, and Pietari Nuutti, who was better known as “Antin Pieti” (pp. 39-41).

Raattamaa is in some respects even more significant to the movement than Laestadius himself. As discussed below, it was he who “discovered the keys” with the proclamation of the forgiveness of sins and made use of it despite Laestadius’s reluctance. And he was heavily involved with the early days of Laestadianism in North America. But he seems to have received even less attention than Laestadius.

Here are the two quotes mentioning him that made it into my sample. The first is from a historical sermon published in 1963 by Pauli Korteniemi, and the other is from the History page of SRK’s website:

† “Juhani Raattamaa then came after Laestadius in the North Country as the father of Christianity and to direct Christianity, or as a great prophet of the Lord, or worker in the Lord’s vineyard.”

† “The most effective spreader of the Laestadianism was the missionary school organisation led by the school master . . . Juhani Raattamaa.”

The penitent . . . is led into the midst of the gathering, whereupon, the preacher, putting his hands round the penitent’s neck, in a solemn tone pronounces the forgiveness of sins to the sinner.

—Andrew Wangberg, Bible Pioneer Work in Norwegian Lapland

Laestadius wrote of his 1844 meeting with a Lapp girl “Maria” or “Mary” in an autobiographical article “Concerning the First Causes of the Awakenings” that appeared in The Voice of One Crying in the Wilderness, which I will abbreviate as VCW from this point on.2 That winter, he

came to Åsele Lapland to conduct examinations. Here I met some Readers, who were of the more moderate kind. Among them was a certain Lapp girl named Mary who, upon having heard my communion sermon, opened up her entire heart to me. This simple girl had experiences in the order of grace which I have never heard before. She had traveled long distances in her search for light in the darkness. In her travels she had finally come to Pastor Brandell in Nora, and when the girl opened up her heart to him, Brandell freed her of doubt; through him, the girl was led to living faith. And I thought: “Here is another Mary who sits at Jesus’ feet. And only now”–I thought–“now I see the way which leads to life; it had been hid from me, until I had opportunity to converse with Mary.” Her simple story of her wanderings and experiences made such a deep impression in my heart that the light dawned for me also; I was able to feel that evening, which I spent in Mary’s company, a foretaste of heavenly joy. But the pastors in Åsele did not understand Mary’s heart, and Mary also felt that they were not of this sheepfold. I shall remember poor Mary as long as I live, and hope to meet her in a brighter world on the other side of the grave. [VCW, 36]

This was certainly a definitive conversion experience for Laestadius, but it is remarkable that he declines to mention anything about Mary proclaiming the forgiveness of his sins when he writes of the event, sometime after 1853. Rather, he attributes his “dawning of the light” to the impression made in his heart by the “simple story of her wanderings and experiences.” In Lars Levi Laestadius and the Revival in Lapland, Hepokoski writes:

Although it is assumed by some who consider themselves followers of Laestadius that he confessed his sins to Maria and that she freed him by proclaiming absolution, he nowhere indicates that anything like this took place. His focus is not on his own experiences–which he may indeed have shared with her–but on hers, and by hearing her story he saw the light. Furthermore, individual absolution was not practiced by laymen during the first six years of the revival, and if the Pastor himself had been absolved from his sins by a “simple” Lapp on that day in 1844, there could have been no subsequent discovery of the keys. [p. 9]

In 1872, Raattamaa wrote of the event with an added detail that at least hints at personal absolution. He said that Laestadius became contrite and sought for salvation, but “did not understand it until the Lapp maid Mary told him that he, in the condition in which he now was, must believe his sins forgiven. He then comprehended peace by faith, and began to preach with the power of the Spirit” (from Kulla 1993, 72).

In his description of Laestadius’ conversion, Raattamaa wrote that he himself “also became awakened at about the same time” (Kulla 1993, 72). In his compilation of Background Writings and Testimonies from the Laestadian movement, Warren Hepokoski states that Raattamaa’s conversion occurred in early 1846 and translates a biographical article on Raattamaa, originally published in two issues of the early periodical Kristillinen Kuukauslehti, Dec. 1881 and Jan. 1882. The article describes Raattamaa’s battle between an awakened conscience and recurring sin, especially drunkenness, over a period of some six years. Then, the article quotes Raattamaa as saying,

It made a vivid and deep impression on me when Pastor Laestadius spoke with me in a gentle and loving manner and recalled how a certain Lapp girl had set him straight. He also said that it is self-righteousness that prevents the penitent from receiving the grace of God in Christ. This tender speech aroused in me a hope that God might be graceful even to me for the sake of the name of his only begotten Son. From that moment, like the prodigal son, I came to myself, and I felt the love of God the Father, that my immortal spirit wouldn’t perish. [p. 33]

Raattamaa still felt, though, that his “sins weighed heavily on the Son of God and are the iron nails that the soldiers drove into his hands and feet on the mount of Golgotha. This was followed by deep sorrow in my soul over my sins, and the awful sin of unbelief revealed itself. I also feared that I had committed the sin against the Holy Spirit. However, I didn’t despair, as I had at 16 years of age, but I clung firmly to the intercession of the Lord Jesus, who prayed: ‘Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.’” He promised God “during moments of prayer and devotion, night and day” that he “would teach transgressors his ways so that sinners would repent, for general impenitence and drunkenness had overcome the men and women of Lapland” (p. 33). He was

in this condition nearly two years. Occasionally I was comforted by the gospel. Otherwise I would not have had the strength to live and preach repentance to others.

But when, in faith and spirit, I was allowed to view the blood-red, thorn-crowned King, power issued from Him, and Christ’s suffering effected a living power in my soul. I believed my sins forgiven in the shed and sprinkled blood, and this was followed by a knowledge of the risen and living Lord Jesus. That which I had sought afar was indeed near and effected joy and peace in my soul. I had thought even previously that I believed Jesus had died and risen from the dead, but now I was ashamed of my unbelief and realized that previously I hadn’t believed from my heart after all. [pp. 33-34]

Raattamaa mentions being “comforted by the gospel,” which in current Conservative Laestadian parlance equates to the proclamation of absolution. But he seems to connect believing his “sins forgiven in the shed and sprinkled blood” with a vision of Christ crucified in “faith and spirit.” In another account, Raattamaa described great joy coming to him when Laestadius “conducted services in the church, and there within was sung” a hymn, “In my great distress I cry up to the Lord.” Then, he writes, “when I felt joy and Jesus appeared to me with His love, I had to believe, even if I had not wanted to” (Father’s Voice II, 238). In neither place does Raattamaa mention any proclamation of absolution from Laestadius or anyone else.3

Juhani Raattamaa’s brother Peter experienced “the day of redemption” in March 1846, as Laestadius wrote of it several years later:

He was outdoors and paced back and forth along the river, for he lacked the strength to do any particular work. In the midst of his walking, a few words of grace struck his heart like lightning, and in the same twinkling-of-an-eye he felt an inexplicable joy streaming through his entire inner being. [VCW, 79]

In an 1882 autobiography, Erkki Antti Juhonpieti recalled his conversion as an event that began with five years of struggle with an awakened conscience, a visit with a “repentant man” who came to visit him around 1849, and subsequent reflection and reading. The 1849 date is based on Juhonpieti’s recollection that he was 35 years old at the time, and that he was born in 1814 (Kulla 1993, 79 and 81). He and his visitor

talked together of what we understood of the way of salvation. That evening after he went home, death and judgment stood before me and I had great sorrow over my condition. I then beheld the Savior nailed to the cross, from which sight my conscience became greatly distressed, and I wondered if God would still accept me and if there still was time to be saved, before death cut the thin cord which held me from falling into hell, which was burning with fire and brimstone. . . . In that time of distress I read and prayed that God would help, if God could still find a place in me. [from Kulla 1993, 81]

He read a book entitled “The Order of Grace,” and “the promises of grace and the gospel opened to me, that if you believe on the Lord Jesus Christ you are saved.” But then

came unworthiness, that how is it fitting for me to believe when I haven’t yet had true penitence or repentance? I will become a hypocrite. But the spirit of God, who is the Beginner and Finisher of faith, went internally through that Word that had been read, saying that if you don’t believe you will go to hell, no matter how penitent you might be. Fear was great, but there was also hope. Then I took firm hold of the promises of grace, and in the proportion that I believed, I felt peace and rest. I also felt joy, and I was allowed to see Jesus in the glory of victory for the first time, when I was able to believe that I was saved. [p. 81]

Again, there is no mention of any proclamation of absolution. Indeed, Juhonpieti makes it quite clear that he was not “allowed to see Jesus in the glory of victory” or “able to believe that he was saved” until well after his visitor had departed.

Things changed dramatically sometime around 1851-1853, when Raattamaa found himself confronted with a girl who remained in distress of conscience even after his evangelical teaching. On that occasion, he made a “discovery” of the “keys of the kingdom of heaven” that would change the experience of conversion and form a fundamental doctrine of the Laestadian faith. After its 1846-1847 beginnings, the Laestadian “spiritual movement had spread for six years already before I really understood the freedom,” Raattamaa recalled in 1881, confirming the date.4 “Since then, I and some brothers and sisters have put the keys of the kingdom of heaven into use, by which troubled souls began to be freed and prisoners of unbelief began to lose their chains, and they rejoiced in spirit” (Hepokoski 2000, 9-10).

As recalled by Erik Johnsen, who claimed Raattamaa told him about the event in 1894, Raattamaa

was just leaving to go home. The reindeer was harnessed and standing before the door. Many people had gathered at the house. Some were already in living faith. But one girl was moaning due to a troubled conscience. Raattamaa and others preached to her about faith and the gospel, but she could not appropriate faith and was not comforted. Raattamaa put his coat on, bade farewell to the people, and went out the door; but then he turned, went back into the house, and asked the girl, “Do you believe that we are God’s people?” The girl answered boldly, “I believe with all my heart that you are God’s people.“Again Raattamaa said, “Then you believe what we say to you in behalf of God.” She responded, “I believe.” Then Raattamaa went to her and placed his hand on her. When he had declared the forgiveness of sins to her, the girl was so overcome with joy that she began praising God. (Leivo 2005, 126-7)

Raattamaa wondered “whether he had done the right thing,” but was reassured when he arrived home and consulted his New Testament. It opened to John 20, “which tells about how Jesus blew on his disciples and said, ‘Receive ye the Holy Ghost: whosoever sins ye remit, they are remitted unto them; and whosoever sins ye retain, they are retained.’” Then Raattamaa “finally realized that this is indeed the command of Jesus” (p. 127).

This belated realization by Raattamaa, the timing of his “discovery of the keys” and Laestadius’ initial misgivings to it, and the lack of first-hand accounts of the keys being used in conversion before the discovery makes it seem that the early awakenings did not involve the proclamation of the forgiveness of sins from a believer to a penitent one. But that is completely contrary to the Conservative Laestadian doctrine that such a personal proclamation is the only way for one to receive forgiveness of his sins, including the “greatest sin” of unbelief (see 4.2.5 and 4.6.2). It seems like a vexing problem indeed for a church to teach that its doctrine never changes and yet have its founders entering into “living faith” without the benefit of the very proclamation of the forgiveness of sins that is one of its distinguishing characteristics and central doctrines.

Aatu Laitinen, a prominent early Laestadian preacher who eventually became estranged from the Conservatives, provided another description of the event in a 1917 writing:

There was once at services an awakened servant, whose time to return home had come. The hour of departure approached, and her sorrow grew because she had to leave with her load of sin. Raattamaa then asked her whether she believed they were the people of God. She said that she believed. He then asked whether she believed it to be the grace of God if they, on behalf of God, testify the forgiveness of sins to her in the name and blood of Jesus. She promised to believe that too. Then Raattamaa laid his hands on her and declared to this sorrowing soul the most precious testimony that can be uttered on earth, and the effect was immediately evident in the servant’s great joy and rejoicing. So she, praising God, left for home rejoicing in the manner of the royal chamberlain of Ethiopia [Acts 8:39]. From that time on, Raattamaa said, he was convinced that the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven are to be kept in use in the congregation of God for the salvation of men and that repentance and forgiveness of sins are to be preached boldly among all the people. [from Hepokoski 2002a, 37]

In 1884, with the doctrine of the keys firmly in place, we finally see a conversion experience in which they are used, as Heikki Jussila recalls that event in his own life some 50 years after the fact in The Grace of the Caller (1948). He had spent months in distress over his sins and experienced only temporary relief through confession at his local parsonage (pp. 22-23). Then he encountered “a believing seminarian” who “had the gifts and light of the Holy Spirit to explain false righteousness” and “went immediately to ask him for advice. He had the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven. Then happened simultaneously in Heaven that pardon which was given here upon Earth.” Jussila “was able to come in from the outside, into the Kingdom of God” (p. 25).

Penitents are said to be true when, in confession before the people and the preachers, they make a loud weeping noise, with strange and wild gesticulations, and in general behave like people bereft of reason.

—Andrew Wangberg, Bible Pioneer Work in Norwegian Lapland

Laestadius wrote of many mystical experiences, his own and those of his contemporaries. As a child, he experienced sensations of an “oft-smelled odor of death” and dreams in which he struggled with the dead, both of which he looked back on as being “without doubt a reminder or foreboding of spiritual and eternal death” (VCW, 26).

Following his 1844 conversion, his sermons “took on a more strident coloring” and bore “a strange mysticism,” with his parishioners’ hearts beginning “to feel tender, hard, or swollen” in spiritual distress (pp. 36-37). After a year of such preaching, “the first ‘signs of grace’” began to appear. An earthquake was felt “in the same instant” as a “certain Lapp woman, who had long been under the law, became reconciled or graced,” something he connected with trembling of “the underground powers” (p. 43). He considered the “sign of grace” experienced first by the Lapp woman to be “a holy goal for all the awakened but not yet graced souls–an infinitely great and high goal, toward which all who have a troubled spirit should strive” (p. 44). In the following years, he would report,

it has happened, even though somewhat rarely, that men have smelled the foul odor of brimstone, when someone has wailed under hard pain of conscience; they have even seen vapor rising from the mouths of those from whom the odor of brimstone has come. Sometimes light-colored streaks have been seen hovering over those who have been intensely moved or joyous. I myself have seen these light-colored streaks, lightnings, and flashes many times, yet without the ability to decide with certainty whether this has happened outside of myself or within myself; however, it appears to be most believable that the lightnings and flashes, which I have seen, have been in my own heart. On Christmas Eve in 1847, as I was going to church–when I saw the church road full of people–I was struck in my heart by an inner lightning or flash, which I have felt many times in circumstances such as these. The sight of the crowd of people streaming into church, namely, awakened a momentary feeling, which like lightning flashed through my heart, and which was followed just as quickly by an awakening thought: ‘Is it wretched I that must be the leader of these blind ones into eternity?’ A few seconds afterwards, I saw a great, bright flame rising from the roof of the Karesuando church, in a southerly direction. [pp. 49-50]

Forces of evil were believed to have made visible appearances, “as small black specters flying and flapping around the lighted candles in the chandelier” in the Karesuando church, “as a bear, which lay under my bed and tried to lift up the bed,” and a “great dragon showing me his teeth” (p. 50).

Laestadius defended the “Christians’ visions and revelations” against “rationalist theologians” who considered them to be “superstition, imagination, and delusion,” noting that the Bible told of spirits crawling into a herd of swine and casting a youth into the fire and the waters (p. 50). Most of his

awakened hearers of the word have seen the Savior, whether on the cross, or in the garden, or as risen from the dead. And even though the insensitive intellectual can consider visions such as these to be the consequences of highly-agitated imagination, the believer must nevertheless hold them to be real; for reality and religion is precisely in this, that the doctrine of reconciliation becomes alive and clear to the doubting one, even as the disciples had to receive the visible and feelable assurance of the reality of this living Word. [p. 51]

He was impressed by the fact that “the objects appear so clearly and brightly, in definite order and time sequence. Children who have never read the Bible can quote some Bible passages by chapter and verse while experiencing a vision,” and a few “have had the ability to speak in tongues” (p. 55). Vividly describing a woman’s dream visions of Jesus, heaven, hell, and people on the road to both, he marveled “at the clarity of comprehension, the orderliness and clarity of thoughts” (pp. 56-60).

In addition to visions, the mystical “manifestations of living Christianity” (p. 47) around Laestadius included overwhelming emotions experienced by parishioners during services, who filled the church with ecstatic outbursts of movement and utterance that came to be known as liikutuksia. Due to these “high feelings,” which Laestadius held to be “the essence of living Christianity” (p. 46), without which there is only “dead faith” (p. 83), people “shrieked and screamed, rose and embraced one another, swung their arms, jumped, spun in circles, danced and fell in heaps on the floor or even in snowbanks” (Hepokoski 2000, 12).

It’s worth asking whether Laestadius was aware of very similar manifestations and “high feelings” in the “great awakenings,” religious revivals that had been occurring in America, off and on, for 100 years (Mercer 2009, 11-13). At the Cane Ridge, Kentucky camp meeting (see caneridge.org), Peter Cartwright preached over 14,000 sermons and baptized 12,000 people, and would recall in his 1857 autobiography that the “heavenly fire spread in almost every direction. It was said, by truthful witnesses, that at times more than one thousand persons broke out into loud shouting all at once.” In the presence of “a warm song or sermon, “people were “seized with a convulsive jerking all over, which they could not by any possibility avoid,” and would usually “rise up and dance” (from Mercer 2009, 13). I have not come across any indication that Laestadius knew of these events, but if so, he would have needed to either accept the thousands of new converts in America as being in “living faith” (which seems unlikely), or back down from his view that such ecstatic experiences were essential indications of living faith.

Raattamaa was also a participant in the early mysticism, writing an 1873 letter about a trance he had experienced about a year earlier, in which he

saw a brown dragon driving through the air on a brown horse from the south to the north with a great sound and rumbling, so that people were terrified, and brown scales fell to the earth. This is a new reminder to us that the dragon is not a fly, but a roaring lion. After that I saw a great brightness on the western side of the heavens which suddenly spread itself. There was a new heaven and no sun, for all was just as bright; and a great multitude sang sweet hallelujah with a loud voice. [from Kulla 1985, 390]

In a sermon published in 1898, Antin Pieti described “a certain vision, which appeared to an awakened soul.” The visionary “saw hell burning as a foaming rapids, where the condemned heathens were swimming. On the flames of hell was set a great kettle with a lock, which the evil spirit guarded. Then another evil spirit was brought to hell,” which the visionary “said was a soul which once was a Christian, but had not followed the footsteps of Jesus. This soul was put into the flaming kettle, when the evil one opened the cover. Hot fiery flames shot up, and as people endeavored to cling to the sides the evil spirits swiped at them with a great saber, and then closed the lid (Sanomia Siionista, from Kulla 1993, 84).

Also in 1898, after a contentious meeting with doctrinal opponents, Heikki Jussila “fell into a trance and a voice from Heaven said: ‘Jussila, keep what thou hast, that none may take away thy crown.’ Then it opened to me that God’s way to grace is that to which God had helped me from the way of self-righteousness and on which he had also preserved me” (Jussila 1948, 72).

The Conservative historian Mauri Kinnunen has supplied me with a translation of an interesting set of recollections about Laestadianism in the 1860s and 1870s. They were recorded in 1883 by the preacher Erik Stock, based on what his father had told him. They include a vivid description of the deep Pietism and mysticism that was expected at the time:

When Laestadius was still alive, a burning sense of sin was required, one that made you scream for mercy from God. The Elders named a couple things that you had to know as a testimony of receiving the grace. Firstly, you had to know the time and place of the resurrection. Secondly, you had had to have seen Jesus in spirit, suffering, death and resurrected. To those who could figure these out with their experience (even without meaning) was given the testimony of a child of God. Then the power of law was stronger than the power of grace. [from Kinnunen 2012]

After Laestadius’s death in 1861, however, it was felt “that enough law had been preached and that the number of believers had not became as great as they had hoped it would.” The Laestadians felt that the awakenings had concluded, especially among the young, and that excessive sensitivity about the law’s demands left people with a sense that they had no strength to follow suit. So “they started to use grace and forgiveness of sins to make people admit that Jesus is in their hearts and that all the sins have been forgiven for them.” But that

didn’t work too well either, because some were reluctant to say such things. After that, they began to preach forgiveness of sins at services, without asking whether they [the audience] wanted or needed it. Consequently, it looked like it worked well, and that the congregation started spreading at a great pace. However, this effect was like morning dew that disappears before noon. Namely, this was like patching an old garment instead of getting a new one. Also, there was neither knowledge, enlightenment [of the Holy Spirit], unanimity nor vigilance . . . [from Kinnunen 2012]

By 1978, an article in Päivämies would speak quite disparagingly of “signs and wonders”:

† “Into the picture of false prophets, particularly in the last times, belongs not only the performing of small tricks, but great wonders and signs. For this reason, if someone declares unto us that a certain such wonder happened at one of these meetings, and on this basis assures us that the great power of God was in effect there, we can answer, “Whether or not such wonders took place is not conclusive. According to the teachings of Jesus, such wonders will still, and especially in the last times, be associated with the works of false prophets” (from VOZ, 6/1978).

The mysticism that Laestadius valued so highly had fallen by the wayside. It only remained in the form of vocal outbursts of “rejoicing” that occurred during services, a “voice of praise to the Lord Jesus heard from the House of God” that was, in Erkki Reinikainen’s 1969 observation, “a continual object of ridicule” (p. 42). And even that mild vestige of the liikutuksia from a hundred years earlier became less and less frequent until it completely disappeared in the 1990s.

Protestants are still an unsettled bunch. To this day they continue to fight theological battles among themselves; battles that result in increasing numbers of official denominations.

—Calvin Mercer, Slaves to Faith

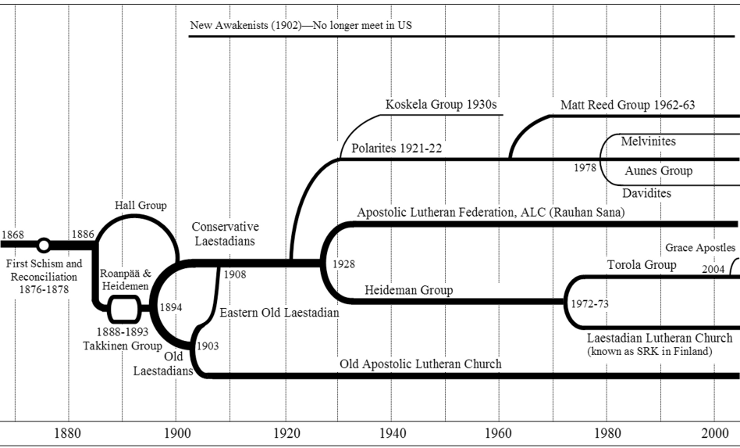

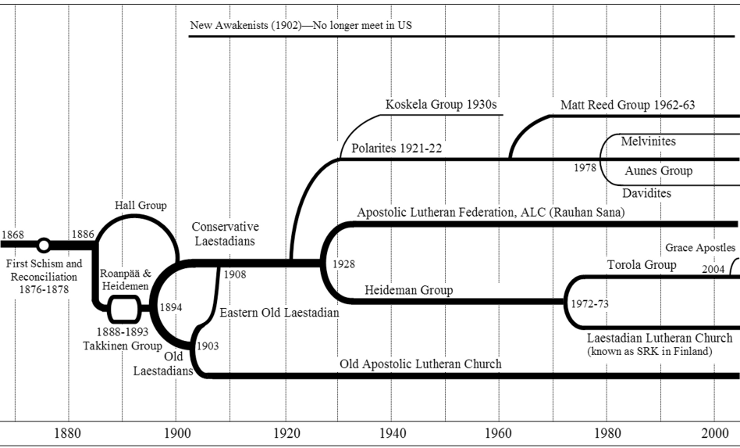

The Laestadian movement has split into numerous separate factions in the past hundred years. This diagram, reprinted with permission from A Godly Heritage (Foltz and Yliniemi 2005), illustrates the timeline of the divisions with approximate size of the resulting groups. (Not shown is a very small schism that took place in the OALC, and two in the SRK, some decades ago.)

The Conservative ordained pastor John Lehtola discusses the history of the various schisms in his 2007 Master’s Thesis, the first of which occurred at “the turn of the century,” when “Laestadianism in Scandinavia splintered into three major groups in three different geographical locations in Finland and Sweden. Until the death of Raattamaa [in 1899], there was formal unity among the different groups, even though differences in doctrine existed. Time and again, Raattamaa was able to reconcile the differences between the groups, but after his death the schisms became a reality. The Eastern Laestadians who lived in the Tornio River valley were known as the Conservative Laestadians” (p. 9). The other two groups were the “Firstborn,” Laestadians west of the Tornio River who claimed (with considerable justification) to follow in the footsteps of the original Laestadian elders, and the “New Awakening.”

“After 1908,” Lehtola continues, “American Laestadianism, or the Apostolic Lutheran church, was divided in three main groups.” The Conservative Laestadians organized as the SRK and were called “the Heideman Group, after their leader,” Arthur Leopold (A.L.) Heideman, and were in spiritual communion with the Tornio River valley Laestadians. The other groups were “the Old Apostolic Lutheran Church, or the First Born,” led by John Takkinen and in communion with the Firstborn west of the Tornio River, and “the ‘Large Meeting Group’” who would later become the Apostolic Lutheran Federation (pp. 23-24). The divisions between the three groups were not entirely complete until the 1930s, and there were even residual affiliations between the Conservatives and the Federation later than that in the Wolf Lake, MN area, with the final division between the two taking place in 1956 (Palola 2010). Until the 1950s, in some remote locations of the Dakotas and Alberta, the Apostolic Lutheran settlements were so small in size that all of the Apostolic Lutherans would join together for services whenever a preacher came from any of the three groups (Palola 2011).

The Conservatives would suffer four other schisms in the 20th century. Although each was mostly confined to one side of the Atlantic, there were connections between the various offshoot groups. In North America, a group of “extreme evangelicals” led by John Pollari, “who did not believe in the need of reproofs and instruction” withdrew and built their own church buildings and congregations, forming the Independent Apostolic Lutheran Church (Kulla 2004, 63). That occurred over the course of a few years around 1920, when the Conservatives still had some ties with the Federation (pp. 63 and 75-76). A 1973 split cost the North American Conservatives most of their preachers and about half of the total membership, who formed the First Apostolic Lutheran Church (FALC) under the dominant leadership of Walter Torola.

In 1934, some Finnish preachers “who had gone to America without approval” were “expelled from the SRK,” and formed the “Small Firstborn,” which now has ties with the Federation (p. 86). A “minister’s heresy” resulted in the departure of most of the SRK’s ordained clergy from 1959 to 1961, forming the “Word of Life,” but that schism had limited impact on total membership. At issue was whether the Lutheran confessions take priority when they conflict with Laestadian ideas. One Finnish pastor with a Conservative Laestadian background told me, “The heresy of pappis [ordained pastors] was that they could not join the heresy formed by lay preachers” in allowing the Lutheran confessions to yield in such cases. In an ironic twist, those “who were in the forefront of expelling” the ordained pastors from the SRK found themselves considered heretics by the SRK and, in 1977, formed their own group that became associated with the FALC in America (Kulla 2004, 86).

Today the SRK is a dominant voice of Laestadianism in Finland, with highly visible spokesmen, publications, and widely attended Summer Services. It has two main rival groups there, whose total membership is only a fraction of the SRK’s. In North America, the situation is quite different–the remainder of the SRK’s remaining counterpart (now organized as the LLC) has four rival Laestadian groups, three of comparable size as the LLC. They are the Old Apostolic Lutheran Church (OALC), the Apostolic Lutheran Church or “Federation” (or ALC), the First Apostolic Lutheran Church (FALC), and the Independent Apostolic Lutheran Church (IALC).

The Firstborn is known in America as the Old Apostolic Lutheran Church (OALC). It is the most conservative of the Laestadian factions. Kulla’s estimate is that the OALC has about 8,000 members and “is possibly the largest group of Laestadians in America (Kulla 2004, 102).

When comparing the different groups, labeling the SRK and LLC as “Conservative Laestadianism” can be misleading, because the OALC is far more conservative in its adherence to the teachings, social outlook, and even language patterns of Laestadius himself. It also adheres to stricter behavioral norms and practices confession as part of absolution much more consistently.

If you want to see 19th century Laestadianism preserved like an insect in a chunk of amber, just attend an OALC service. I have done so twice, at two different localities, and found it a fascinating experience both times. The services begin with slow, mournful singing unaccompanied by any musical instruments and then proceed to a reading of one of Laestadius’s sermons. I sat in the pews surrounded by men in long sleeve western or dress shirts (no ties) and women wearing headscarves and dresses, listening to the harsh, archaic rantings of Laestadius about whores and grace thieves and wondered if I had stepped into a time machine. Things didn’t lighten up much from that point, either.

The sermon reading was followed by a long pause as the congregation’s entire cohort of preachers–all sitting in chairs several feet behind the pulpit and facing the congregation–awaited the inspiration for one of them to take the helm for a live sermon. Finally, one stepped forward with a great show of reluctance, sat down, and asked for a text to be read by another who joined him at the pulpit. Then began a full ten minutes of drama as the preacher mournfully lamented his unworthiness to expound on the great words already provided by the elder Laestadius. Perhaps some words might still be given, he at last allowed, and sure enough, I sat through another 40 minutes or so of traditional, repetitive exposition of the text, line by tedious line.

If the Book of Mormon is “chloroform in print,” as Mark Twain put it, then those two sermons were the audio version. Most of those under the age of about 15 seemed oblivious to what was being said. (They had tuned out the Laestadius reading entirely.) I remained awake mostly because of how interesting I found the parallels to be between the sermon and those I had grown up listening to in the late 1970s. I noticed a number of phrases that are still used in LLC sermons, e.g., “living faith,” “a new day of grace,” “we want to be obedient.” Interjections like “I believe,” “even,” and “we could say” were scattered throughout the sermons as a sort of verbal curtseying before God who was, after all, the one providing the words. The public proclamation of forgiveness–the “general blessing” to the assembled congregation–was present, too.

Like the sermons of my childhood, the delivery had a sing-song cadence that is almost hypnotic. As the preacher grows more and more emotional, the high notes get louder and the cadence quickens. Everybody knows what is coming–subconsciously or otherwise, they start feeling the spirit as well. Finally, the preacher tearfully confesses his own sinfulness and the congregation preaches absolution to him, as he did to them a few moments earlier. (In the OALC sermons, the preacher also turned to his pulpit companion for absolution.)

It seemed to me that the emotionalism was a bit forced in the OALC sermons. I would not be surprised if the OALC’s devotion to tradition is motivating both its preachers and its members to produce the appearance of a pietism that isn’t always genuinely felt. Still, the next thing that happened in the OALC services was a genuine spiritual experience for at least a significant part of the congregation. Immediately after the congregation preached the words of absolution to the preacher, perhaps a third of the congregants confessed and preached absolution to each other in the pews and aisles. For 10-20 minutes, the sanctuary was filled with the sound of confessions–in voices that often took on a plaintive, wailing sound–and the preaching of forgiveness in response. The keening sound of women rejoicing could also be heard, and I saw a lot of people wiping away tears, men and women alike. During all of this, the preachers remained at the front of the sanctuary behind the pulpit, standing to receive the 5-10% or so of the congregants who felt the need to go to one of them for absolution.

During these encounters, women embraced and men stood with one hand on each other’s shoulders. The amount of time they spent indicated to me that there was always some sort of a confession, not just the general request for “a blessing” that occurs among Conservatives. (In the LLC, that now consists mostly of turning to your spouse or friend at the communion rail and–if you are not too young or bashful–occasionally raising your hand during a particularly emotional part of a sermon.)

In none of this can I find cause for Conservative Laestadianism to condemn the OALC. Perhaps one might charge that the OALC lapses into idolatry with its zealous esteem of “the dear precious elders of Swedish Lapland” who all reside in Gällivare, Sweden, and in its belief that Laestadius is the seventh angel of Revelation, a prophet it refers to as the “firstborn” (not to be confused with the name of their movement). He is set apart even from the Gällivare elders, who themselves are above the lay members, congregation elders, preachers, and missionary preachers of the OALC’s strict hierarchy. But as a Conservative correspondent remarked to me, “They have their elders, and we have the Mother congregation” (see 4.4.4).

The condemnation between the OALC and the Conservatives is a mutual feeling. They consider each other heretics, bound for hell just like everybody else in the “dead faiths” of the world. The introduction to the OALC’s History of Living Christianity in America (1974) provides a glimpse of its view of itself in opposition to everyone else:

Throughout North America the true Laestadian or living Christianity is flourishing. All those who have sought and found the truth have entered into the one Sheepfold through the door, Lord Jesus. There, under the care of the one Shepherd in the Church of the Firstborn, have they found peace and rest for their immortal souls. There they have received the indwelling Holy Spirit and the love of Christ, and there they stand united in one-mindedness and love, in the bosom of the true Mother.

Let the winds of false doctrine below, let the waves of ungodliness roar, they stand firm and secure for they have a sure place of shelter and refuge. They need not fear nor be in great distress as so many of those who grope about in blindness in the various factions, not knowing which way to turn nor what to hold onto.

The book makes an oblique reference to Conservative Laestadianism when discussing the history of the OALC in Brainerd, Minnesota and recalling “some of the terrible trials that beset the living Christianity”:

When another spirit began to work in man, which was opposed to the spirit of God, great harm was done to God’s work in the hearts of many innocent ones. So it was in Brainerd also, that the spirit of opposition to the truth lead the greater number away, leaving only a few clinging to the original doctrine with full trust upon the Elders of Swedish Lapland. [p. 7]

Brainerd was probably the last place where fellowship continued between members of the OALC and the Conservatives. It was actually a three-way relationship of lingering Laestadian ties that included members of the Federation as well. Two of those Federation members are Carl and Martha Kulla, who were born in the area in 1920 and 1927, respectively. They both recall the common fellowship. “We were all just Christians,” Carl told me in one of my visits to their Brush Prairie, WA home. Martha sadly told a story of her little friends in the Conservative group finally coming to her one day and saying they had needed “to repent of considering her a Christian.”

Another OALC reference to the other Laestadian groups is found in a 1953 article by William Eriksson:

For those, who have completely separated themselves from the truth of the original doctrine, even though they labor in the name of Laestadius, labor not within that doctrine or follow it in faith, doctrine, and striving, but labor together with dead Christendom. They have by name dispersed into many different groups and factions, yet all have the same spirit with the world and permissibility to commit sins, such as finery, friendship with the world, greed, fleshly freedom and lordly Christianity, against which they have not dared to preach severely, because the world and dead Christianity would be offended. . . . However, there is still one flock which wants to follow the original truth of the doctrine in life, in walk and in faith . . . [The Father’s Voice, 324]

Eriksson’s comment about “the original truth” leads to an uncomfortable issue for Conservative Laestadians: Raattamaa, the successor to Laestadius, was firmly in support of the OALC and their first leader, John Takkinen. While the Conservatives and the OALC consider each other heretics, both claim Raattamaa as their own. Though he is himself a Conservative, Tuomas Palola presents a history that appears quite unfavorable to the Conservative position in his 2000 Master’s thesis:

Raattamaa wrote already in January 1889 to Takkinen, who had been removed from the pastor’s office, and stated that he still had the support of the Scandinavian Laestadian leadership. During spring in 1889, the Scandinavian Laestadian leadership took a stand repeatedly in their letters to North America supporting Takkinen: Takkinen “has been sent by God,” and, although “he may be driven out of the Calumet parsonage, he will not depart from the firstborn congregation,” which will protect him. . . . When he received a description of the events in Calumet from Takkinen, Raattamaa especially criticized Hietanen, Juola, and Jacob Vuollet for opposing Takkinen. Raattamaa and Juhonpieti admonished the Apostolic Lutherans toward reconciliation. [Palola 2000, 48]

During the summer of 1889, Raattamaa continued his defense of Takkinen, writing

to Takkinen and Henrik Koller (1859-1935) in Calumet. According [to] Raattamaa, the “persecution” of Takkinen was caused by the fact that Takkinen was the “real preacher of the gospel.” Takkinen was not to give in because he lost the keys to the Calumet Church, for “the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven are more important than the church keys, which the official clergymen can keep.” At the same time, Juhani Raattamaa marveled in a letter that he sent to his son, Peter Raattamaa, how he could be against Takkinen. Juhani Raattamaa admonished his son toward reconciliation with Takkinen[,] . . . emphasized the firstborn congregation[,] . . . and stated that “they who are in fellowship with it will not follow the dictates of a newborn sect.” . . . In Raattamaa’s opinion, those who had struggled against Takkinen were not appropriate to be sent to America. [pp. 49-50]

When A.L. Heideman (who would lead the Conservative group after 1908) stated his intention to go to America during these doctrinal disputes, Raattamaa

said to Heideman that the Apostolic Lutherans did not want an ordained clergyman, especially those who were in agreement with the firstborn congregation. Heideman had stated to Raattamaa that he would go to America as a secretary, and not as a clergyman. Raattamaa reported to America that he had not sent Heideman even as a secretary and thus avoided giving support to Heideman. In addition, Raattamaa stated that only Lumijarvi and Takkinen had been sent by the firstborn congregation, and Daniels, Starkka and Koller were “approved otherwise.” Raattamaa reported that he trusted the supporters of Takkinen the most. Only a few days later, Raattamaa clarified his impression of Heideman: Heideman was a true Christian, but young and had recently repented, and for that reason the firstborn congregation had not wanted to send him to North America as a representative of the firstborn congregation. [p. 52]

Raattamaa didn’t condemn Heideman; he did declare him “competent to preach to the ‘sorrowless’” (p. 52) and, when Heideman and his traveling companion had arrived in Calumet, “admonished them to be considered as ‘precious’ brothers” even though they “had not been sent by the firstborn congregation” (p. 54). Even so, he

used strong language regarding the opponents and wrote that “piggish animals want to destroy the wall of the vineyard which Takkinen has built and cared for over a decade.” He admonished his son, Peter Raattamaa, to repent before Takkinen. Raattamaa could not understand how such men could rise from Laestadianism who did not approve of Takkinen. [p. 54]

In March 1891, after Takkinen’s group had lost ownership of the Calumet church to Heideman’s group (Lehtola 2007, 13-14), Raattamaa still “encouraged the supporters of Takkinen to continue their work: although the church was gone, the true preachers have not gone. In April, Raattamaa repeated the thought: ‘We do not obey sects nor sectors, but we remain in the bosom of the firstborn congregation’” (Palola 2000, 57). Later that year, Raattamaa wrote to Takkinen rejoicing of his retaining many supporters, “although ‘the clergy prepared in colleges’ had started to break up the congregation” (p. 59), and marveling at how the Americans could have been offended in the name, ‘firstborn congregation’” (p. 60).

Takkinen died unexpectedly in February 1892. “Raattamaa admonished both parties involved toward reconciliation when he reported Takkinen’s death” and “wrote as his own viewpoint that the [Calumet Firstborn] congregation should elect a pastor from among the supporters of Takkinen” (p. 63). In an 1892 letter following Takkinen’s death, Raattamaa made his conclusions clear about Takkinen’s eternal fate: “Yet we remember our beloved brother and fellow laborer, John Takkinen, with sorrow and joy, even though his body is resting in the bosom of his Fatherland, but his glorified soul is rejoicing in the Paradise of God” (from Kulla 1985, 393).

In 1898, less than a year before his own death, Raattamaa addressed a letter to a number of Takkinen supporters, calling them “beloved brothers and faithful workers in the Lord’s Vineyard” (from Kulla 1985, 395). They included Matoniemi and Ojala, two Firstborn pastors who had succeeded the deceased Takkinen (Palola 2000, 82) and Koller, who five years hence had begun using “the paper Siionin Sanomat that he published to assist him more clearly in his attack against the congregation led by Heideman” (p. 68). In the letter, Raattamaa sent “greetings of love” to Heideman and his preaching companion, Rajaniemi, and said, “Yet I remind, preach the sermon of reconciliation. Forgive and believe the sins of controversy forgiven. Don’t judge one another for all kinds of faults” (from Kulla 1985, 396).

Today, Conservatives consider Takkinen and his Firstborn group (now the OALC) to be heretical, but Raattamaa never held that view. As Palola concludes, albeit with some caveats about potentially incomplete information to or from Raattamaa, “[b]ased on preserved letters it appears that in the ‘crisis of two churches,’ Raattamaa clearly placed himself in support of Takkinen and the Old Apostolic Lutherans” (Palola 2000, 71).

During my first visit to an OALC service, I wound up discussing some of this history during the dinner they provide afterwards. It was an odd feeling to be surrounded by Laestadians gently prodding me about my unsaved status, considering my group one of the heretics who had left the original Christianity. The nerve of them, when of course it is they who are the heretics! We had an interesting and cordial time, though, talking about arcane topics like the Heidemans booting the OALC out of the Pine Street church in Calumet, Michigan a hundred years ago like it was yesterday’s news. (Me, with a smile: Yep, we sure did.) And, despite their understated manner, they seemed surprised at my willingness to concede that the OALC is the group following in the footsteps of the original elders. As I have found throughout my research for this book, facts are facts whether we like them or not.

Heikki Jussila spent a considerable part of his preaching career battling the New Awakening. He compared it to a storm that, in 1896 “had burst throughout the land even to the outermost areas. . . . It tried the foundations severely, wishing to rob faith and hope from everyone. It sought to examine and condemn everyone. Because it had a different spirit and doctrine, it did not recognize the work of the Holy Spirit nor consider it correct. It prohibited the forgiveness of sins in the name and blood of Jesus. It ridiculed the doctrine of absolution in justification and elevated inner imaginations in its place” (Jussila 1948, 71). “The most sorrowful matter of all,” Jussila writes, “was that in the New Awakening it was taught to reject the former Christianity by repentance and that they spoke mockingly of the blood of Jesus in absolution” (p. 78).

Jussila was given to hyperbole, but the New Awakening was certainly a soul-searing, pietistic movement that did have a legalistic inclination, as acknowledged by one defender quoted in a 1973 lecture: “We have been warning against hypocrisy and dead faith for so long that we don’t dare to believe at all” (from Kulla 2010, 128). One can get an idea of how emotionally demanding it was to the penitent from the following passage by one of its founders, Mikko Saarenpää, written in 1912:

Preciously redeemed souls cannot be freed from these bonds of the devil in any other way than by awakening from sin, and, as in the time of John the Baptist, confessing their sins, becoming naked, open, and honorless. Let it be known, wretched men, that you cannot go to heaven with your honor; you must be shamed, despised, and persecuted by the world. You cannot go from a joyful world to a joyful heaven. You must weep and cry for yourself and your children, as Jesus said on Good Friday to the women and to His disciples. [from Kulla 2010, 50]

Consider, though, that Conservative Laestadianism in decades past has used much the same type of pietistic language, as did Laestadius. See the quotes from earlier years in 4.2.6.

There was an effort at reconciliation in 1911. “The New Awakened were accused of withholding forgiveness from people, but when they did ask forgiveness, for statements and harshness of words, forgiveness was withheld from them” by the conservatives (Kulla 2004, 93). As of 2000, they had membership of about 3,000 in Finland (p. 95). “It is no longer an awakening movement,” having “been almost entirely assimilated into the national Lutheran Church of Finland” and with none remaining in America (Kulla 2010, 5).

The schism with the “Large Meeting Group” slowly erupted among the Eastern or Conservative Laestadians from the 1920s into the 1930s. According to Lehtola, the

main doctrinal difference between the Heideman Group and the Apostolic Lutheran Federation concerned the “doctrine of the church.” The Federation wanted to grant all Laestadians freedom to attend the services of any Laestadian group they desired, and were dissatisfied with a “narrow party spirit.” They urged all Laestadian groups to show more love to one another, for God had children in all groups who must someday get along in the same heaven, they claimed. In heaven there will be no party boundaries, they stated. All God’s children will be united there. The Federation adherents greeted the Heideman Group members with “God’s peace” and kept them as spiritual brethren, but the Heideman Group members refused to reciprocate. The Heideman Group did not consider them as spiritual brethren, for God had children in only one outwardly determinable group.” [2007, 24]

The same positions remain held by the three groups to this day. The Conservatives and the First Born consider each other and the Federation heretical, while the Federation offers its unrequited acceptance to them both.

I have had the privilege of becoming friends with a wonderful old couple in the Federation, Carl and Martha Kulla. In four visits to their home, I have been able to learn some of the facts of church history that Carl holds in such amazing depth and accessibility in his 90-year old brain. But I also learned something that my history books about Laestadianism failed to fully convey: The fruit of the spirit (”love, joy, peace, longsuffering, gentleness, goodness, faith, meekness, temperance,” Galatians 5:22-23) is to be found among other Laestadians as well. As I sat at the Kullas’ little kitchen table and in their living room, hearing their stories and testimony of unfeigned faith, being greeted with “God’s Peace” by some of their many grandchildren who stopped by the house, my already waning belief in the exclusivity of my own particular group flailed about in search of support that I could no longer find.

Carl has reached out to the LLC in the same way he has to the other Laestadian groups. Copies of The Voice of Zion arrive at his home along with the FALC’s Greetings of Peace and his own group’s Christian Monthly. He has attended the LLC summer services as well as local services in Longview, WA. He has visited and written to the LLC offices, telling of his struggle in writing a letter to an LLC preacher in October 1997 “because I accept you as a brother in faith, but I realize that for you this is impossible.” Yet he would “not ask you to do otherwise than your conscience allows.”

Responding in a November 1997 letter, the LLC preacher acknowledged that his “conscience will not allow me to accept you as a brother in faith.” He declined to cite any reason for that judgment (and let’s call it what it is), admitting that he had “not lived through nor witnessed firsthand any of the heresies that have torn living Christianity.” But, he was “nonetheless certain that they have been caused by true differences in spirit and doctrine. Surely, you must recognize this as well.” Why was he so certain that the schisms were not caused by something else, e.g., the divisive leaders of the era, misunderstandings, and prejudices? Because the LLC’s view of its history and exclusivity (4.2.1) had fixed his conclusion firmly in place. His unspecified spiritual and doctrinal differences are the roads that all lead to Rome, and, unsurprisingly, he does “not believe that these can be dismissed as insignificant nor that unity can be purchased at the expense of doctrine.”

What the LLC preacher does dismiss as insignificant are all of the fruits of faith present in Carl’s life along with the signs by which Luther said a “Christian, holy people” could be identified (WA 50, 628). Unlike Luther, the preacher is not at all “certain that where the Gospel is preached, there must be Christians” (PE 4, 75). Instead, he is certain of his own superficial observations during a brief visit Carl had made to the LLC office, where the preacher “was left with the impression that you were a man who recognized his sinfulness and despaired of it, but who was not confident of his salvation and did not possess the peace that Christ gives His own.” As someone who has taken the time to get to know Carl, to sit down with him for hours and hear him speak of a humble and heartfelt faith, I shake my head in disgust at the arrogance of this statement. Unfortunately, we will encounter many more like it in 4.2.3.

The LLC preacher continues: “Knowledge of Christ and His redemption work is not at all the same thing as faith in Him and His work.” You might well ask, what’s the difference? It is the preacher’s encoding of “faith” to mean a manifestation of the Holy Spirit that is only in the LLC (see 4.5.3). “It would be my great joy to someday receive you as a brother in Christ,” the preacher concludes, “but I am convinced and firmly believe that it can only happen if you repent from the heresy in which you are presently entangled.”

That kind of “repentance” seems more like an oath of loyalty to a new allegiance than a turning away from actual sin and unbelief. It’s not a unique demand of Conservative Laestadianism. In the Christian Convention Church, for example, converts are required to “renounce any previous ‘born-again’ experience while in another ‘Christian’ church, saying that it was an emotional experience of Satan” (Lewis 2004, 10-11). Anyone wanting to join “who has believed in Jesus before he heard the True ministry is not allowed Fellowship until he admits that he had not received Jesus before he met the workers. They want to hear the new member declare that all his previous Christian faith was wrong. That is their view of ‘repentance’” (p. 11).

One of my visits with Carl and Martha was in the company of two other LLC preachers, whom I brought along in hopes that some sort of acceptance could be had. But those preachers, who went there more to speak than to listen, soon found themselves being preached back to on every point. During the drive to and from the Kulla home, we had discussions of Carl’s spiritual state that seemed to me to quickly devolve into circularity. “Why is Carl not ‘believing,’ when he accepts the preached proclamation of forgiveness, including when he hears it at LLC services and when I preached it to him?”, I asked. The answer: “Because he does not ‘comprehend the doctrine of the Kingdom.’” To which I said, “I don’t ‘comprehend’ that doctrine either, so why I am I ‘believing’?” There was no satisfactory answer. When confronted by the awkward case of a person who accepts the forgiveness of his sins as preached from “God’s Kingdom” but not the need to forsake his existing non-LLC Christian fellowship, the LLC exclusivist resorts to the tautology that one is not “in the Kingdom” simply because he is not “in the Kingdom.”

I would also inquire about the spiritual state of the LLC’s “doctrinal father” Luther, who quoted Jesus the same way Carl answered the LLC preachers (“The kingdom of God is within you,” and “cometh not with observation”), and who asked how he could “deny Christ, Who clearly says here that there is no locality, place or anything external in the kingdom of God.” See 5.2 for the full quote and many others like it. If one must acknowledge the walls as well as reside within them, as discussed in 4.2.1 (“No Compromises”), the Laestadian Lutheran Church must condemn the man whose name is part of its own.

The First Apostolic Lutheran Church (FALC) was formed by Walter Torola and his followers as a result of a 1973 schism with the Conservatives. (Torola had a very forceful presence, as did his son Peter, and I don’t think it’s unfair to characterize the group as comprised of a leader and followers.) The split occurred after several years in which